When I finished part one of the write-up of my trip to Guatemala two nights before starting this sequel I thought I had just a cold, thanks to pushing things a bit too hard over the past week. Well, that sneaky bastard COVID has finally gotten to me, just as it has mucked with the rest of the world, and now I'll have four or six or whatever days by myself to write and edit—and it is Christmas Eve, to boot! Thankfully, at this point I feel just fine, and even yesterday's runny nose and the slightly sore throat have already vanished. Let's hope that the Paxlovid that had accompanied me on all my trips since last fall will continue to stave off any worse outcomes.

Guatemala—how in the world had I managed to ignore this beautiful, oh-so-colorful, unpretentious country for all those decades? For some reason I kept traveling to both Mexico and Costa Rica but left Guatemala by the wayside. I honestly don't know why. The state of Chiapas in the south of Mexico shares not only the same indigenous roots but also a similar topography with Guatemala. You may remember how much I gushed over my visit to Oaxaca two years ago; but why have I not been back to San Cristobal de las Casas, even a little closer to the Guatemalan border? I had visited the ruins of Tikal, but I've never been to Coban, in the same region, even though I've been countless times to the Riviera Maya. Well, I guess I'll have to do something about that in the next few years.

|

| Casa Byron as seen from the water |

For the week that I spent in Casa Byron on Lake Atitlán I was free to do whatever I wanted to do—no particular time to get up, no bike to ride, no schedule to follow, no particular time to turn in at night. Yet every day brought new experiences as every night I was actively looking at how I'd spend the next day. Even though my hip implant means that my range of motion and mobility in the right leg have been affected it doesn't mean that I can't walk and hike any longer. Sure, at the end of a day of hiking for 8 or 10 miles with elevation changes of 2,000 feet or more that right hip feels tired and even worn out, but most folks my age would feel the same way (or they wouldn't even embark on a journey on foot). Once I had started to plan this trip it had been clear that I would be on my feet for much of my waking hours.

While most of the streets in Tzununá (where Casa Byron is located) are paved, once you leave the town proper all three roads are rough and unpaved. From the edge of town where the concrete ends it is less than half a mile to Casa Byron, but the trail quickly deteriorates and can't be called a road. Walk (or drive, but not in my car) another quarter mile and the steep road ends and becomes a footpath that eventually will lead you to Jaibalito. One day I took this route, and it was as if I had been teleported back a hundred years or more. The path is narrow, steep, and curvy, hugging the cliffside, with incredible vistas of the lake. It is "maintained' by locals with machetes who clear the trail from vegetation and take over the role of the mowers that we see clearing the right-of-way of our highways. Sometimes it was unclear to me how they could manage to keep their footing on those steep slopes, all the while hacking with their two-foot-long knives.

While most of the streets in Tzununá (where Casa Byron is located) are paved, once you leave the town proper all three roads are rough and unpaved. From the edge of town where the concrete ends it is less than half a mile to Casa Byron, but the trail quickly deteriorates and can't be called a road. Walk (or drive, but not in my car) another quarter mile and the steep road ends and becomes a footpath that eventually will lead you to Jaibalito. One day I took this route, and it was as if I had been teleported back a hundred years or more. The path is narrow, steep, and curvy, hugging the cliffside, with incredible vistas of the lake. It is "maintained' by locals with machetes who clear the trail from vegetation and take over the role of the mowers that we see clearing the right-of-way of our highways. Sometimes it was unclear to me how they could manage to keep their footing on those steep slopes, all the while hacking with their two-foot-long knives.

On the trails I encountered mostly women and girls but also a few men and boys transporting on their backs large loads of firewood and oversized nets containing gourds. If you can't use a pick-up and you don't have a donkey you have to carry stuff on your back, all supported by the tumpline on the forehead and one hand (sometimes both) toward the back to stabilize the teetering load. One can see the neck muscles and veins bulging from effort. Yes, this is the year 2022, yet these hard-working people use methods of transportation that go back millennia. Talk about a reality check.

On the entire trip I saw only one or two burros that were used to transport immense loads of firewood. Both were led on a rope held by what seemed to be an octogenarian carrying an almost equally large pile of wood. All other loads that I saw outside areas that had some sort of "road" accessible to tuk-tuks or pick-up trucks were carried by humans—young, old, ancient, boy or girl, man or woman. Similarly, I saw men working in creek beds, hacking loose and cleaning rocks. It wasn't quite clear to me how these rocks would later be used, but they were put into canvas bags for eventual transport. Humans take on the role of equipment, and almost nobody seems to be too young or too old to work.

There's a lot of ingenuity one can observe. On one of my walks, for example, I came across a group of three workers, two of whom were holding up a ladder that a third worker clung to while tying some rebar for a future concrete pole that would hold an electric meter (see photo below). On another day I encountered another, similar group, that was holding a ladder in the middle of the road so that some highline repair could be done.

In the towns one can often observe men or women splitting and stacking firewood. Larger trees go to mills that produce boards that are displayed by the side of the calle. Everybody seems to be involved in some activity, and one doesn't see many people loiter. What I found really astonishing was how polite the locals were when I walked by. After making eye contact they'd initiate a sometimes shy, often rather warm smile and offer a buenas dias or buenas tardes. When I greeted first, even the shy ones would look up and offer their own greeting. Little kids were especially enjoyable as there was a carefree air about their buenas dias, señor. It is easy to feel welcome and at home in Guatemala.

I spoke to several ex-pats on my walks, and it appears that some gringos have decided to spend long periods down here, with some buying homes and trying to blend in. One man from northern California told me that living and owning a house in a village means that one becomes accepted, and since nobody owns a car all intermingle, be it on the streets or in shared tuk-tuks or pickups or while taking a lancha. When I asked about medical services in such a remote place he told me that the town (this was in Jaibalito, which cannot be reached via any road) has a helicopter pad and that in an emergency one can be in the hospital in Panajachel within 20 minutes. Routine visits to a physician obviously need to be planned, but maybe it's not all that much different from our small towns in the Texas Panhandle that are a 90-minute drive away from Lubbock.

There's a lot of ingenuity one can observe. On one of my walks, for example, I came across a group of three workers, two of whom were holding up a ladder that a third worker clung to while tying some rebar for a future concrete pole that would hold an electric meter (see photo below). On another day I encountered another, similar group, that was holding a ladder in the middle of the road so that some highline repair could be done.

|

| More ladder ingenuity |

I spoke to several ex-pats on my walks, and it appears that some gringos have decided to spend long periods down here, with some buying homes and trying to blend in. One man from northern California told me that living and owning a house in a village means that one becomes accepted, and since nobody owns a car all intermingle, be it on the streets or in shared tuk-tuks or pickups or while taking a lancha. When I asked about medical services in such a remote place he told me that the town (this was in Jaibalito, which cannot be reached via any road) has a helicopter pad and that in an emergency one can be in the hospital in Panajachel within 20 minutes. Routine visits to a physician obviously need to be planned, but maybe it's not all that much different from our small towns in the Texas Panhandle that are a 90-minute drive away from Lubbock.

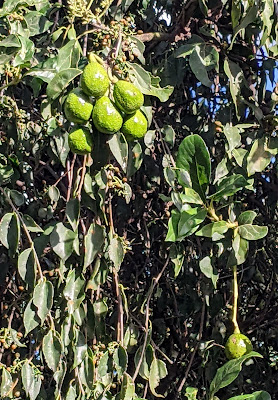

While walking I saw the main agricultural staples of the area, maíz and café. Cornfields are strewn all over the hillsides, and there doesn't seem to be a particular season when it grows. Coffee is different: Its berries start to ripen up starting in November when the first ones turn from green to red, indicating that they are ripe for harvest. For the next four months they will be handpicked whenever they have reached their desired maturity. Once the red berries have been picked, they are washed and bleached of toxins in water and then dried for several days in the sun before the beans can be roasted. Fun fact: A red coffee berry tastes very sweet and of course contains the two seeds that we know as coffee beans. But don't eat more than one of the red beans as the toxins will give you a stomachache.

Other fruit and vegetables that are grown would be what you see in any one of the street markets: anything from onions and potatoes to watermelons and oranges. Markets are a fabulous source of finding out what the locals grow, and some stuff you may not know. I had always seen chayote, a small, pear-like shaped gourd, but didn't really know anything about it. When I had bought my groceries in Panajachel on the way to Tzununá I had bought some spice mixture to make pollo pipián, and since the recipe called for chayote I picked one up. One peels the chayote with a knife and the inside is white and kinda tart, definitely not like a pumpkin or a butternut squash, gourds in themselves. Then cut it up into small pieces and cook it with potatoes (also in small cubes) and green beans in a mole-like stew with a couple of drumsticks or other leg pieces of the chicken. Damn good!

That's what I kike about traveling: discovering new stuff, of whatever nature it may be. I'm really not a fashion guy, and I actually have a fairly well-enforced moratorium on bringing home "souvenirs" because I already have so many items displayed all over the house. So, when a sign in San Pedro beckoned me to visit the local weavers' co-op I first continued to walk but then turned around, thinking, why not? Maybe I learn something. I was treated to a general introduction into the eons-old craft of collecting cotton, spinning and dying yarn, and then weaving it into those incredibly colorful garments that most indigenous women in Guatemala still wear on a daily basis. The process is simply fascinating, and you can't help but be awed by the perseverance and skill of the women who produce these textiles. Most of the articles in this centro artesanal of course are being bought by tourists (national and international), but I am 100% sure that not a single square inch of the clothing that I saw on all the women and girls that I encountered on my excursions was produced in China—it's all hecho a mano, by a Maya woman who was taught by her mother who had picked up the skill from her forebears. Think for a moment about how cool that is.

Numerous times I have used the word "colorful" to describe Guatemala. This word can have several meanings, but I intend for it to retain its pure and simple definition of being "full of color." The just-discussed textiles are a large part of this colorfulness, as the yarns, historically died by natural means that involved plants, minerals, and even insect larvae, sport a vast array of shades from deep magentas via red to yellows. Colors are in every market—just look at all those fruit! The tuk-tuks as well as the so-called chicken buses are painted in vivid greens, reds, and yellows, as are the boats, the lanchas. Bare walls are begging to be adorned by colorful murals, not the usually subdued (and stupid) graffiti that we see in our cities and those in Europe. The sky is a deep blue, the mountain sides are a satisfying green, and when there are clouds they are a brilliant white. Color is everywhere, and maybe that's why the people have such bright countenances.

My excursion to Panajachel did not involve as much walking and hiking as some of the others. I took the lancha on a Saturday morning with no particular plans in regard to what to do in Lake Atitlán's major town. Upon arrival at the pier it was evident that Pana—as it is universally called by the locals—is a destination for not only gringo tourists but also the local crowd. I simply floated along the beach promenade, whence excursion boats took off for 30- or 60-minute sightseeing tours, apparently very popular with families and elderly Mayan couples seeking weekend entertainment. Ice cream, balloon, corn-on-the-cob, trinkets-of-all sorts vendors were hawking their wares, and polite-yet-persistent barkers tried to lure the crowd into their restaurant. In a large, unpaved lot little tykes could drive electric quads while their proud parents and grandparents silently watched with big smiles on their faces. A paraglider landed just steps away, and two mongrel dogs were awkwardly copulating, for long moments connected thanks to that strange canine anatomy.

Resisting the urge to weigh myself for a quetzal in plain view of everyone I found a spot in a restaurant overlooking the lake. From an adjacent restaurant the noise of an ongoing World Cup soccer quarterfinal was trying to out-do the loud sounds of our jukebox. There probably were some gringos around, but they were not noticeable among the locals who were out on the town on that beautiful day. Feliz Navidad, indeed. I encountered a similar scene, just not as pronounced, on an excursion to San Pedro: pura vida, as they call it in Costa Rica. Once in a while people just like and want and need to let their everyday life slip away for a few hours.

I cannot say that I had a particular "favorite excursion" during my week on the lake as every single one was so different and full of impressions. But when it comes to the toughest and maybe most rewarding outing, I think it was my hike up to the Mayan Nose. I had read up on guided tours to some of the surrounding volcanoes (Guatemala is home to 30+ of them), but too many online comments as well as what Byron had told me convinced me to not pursue such a trip. Apparently there have been instances of hikers being accosted and robbed in the upper portions of these regions, despite being accompanied by local guides. Even though most of the area is a national park, law enforcement is light at best and there are just too many opportunities for a few bad elements to slip in and out.

That's what I kike about traveling: discovering new stuff, of whatever nature it may be. I'm really not a fashion guy, and I actually have a fairly well-enforced moratorium on bringing home "souvenirs" because I already have so many items displayed all over the house. So, when a sign in San Pedro beckoned me to visit the local weavers' co-op I first continued to walk but then turned around, thinking, why not? Maybe I learn something. I was treated to a general introduction into the eons-old craft of collecting cotton, spinning and dying yarn, and then weaving it into those incredibly colorful garments that most indigenous women in Guatemala still wear on a daily basis. The process is simply fascinating, and you can't help but be awed by the perseverance and skill of the women who produce these textiles. Most of the articles in this centro artesanal of course are being bought by tourists (national and international), but I am 100% sure that not a single square inch of the clothing that I saw on all the women and girls that I encountered on my excursions was produced in China—it's all hecho a mano, by a Maya woman who was taught by her mother who had picked up the skill from her forebears. Think for a moment about how cool that is.

Numerous times I have used the word "colorful" to describe Guatemala. This word can have several meanings, but I intend for it to retain its pure and simple definition of being "full of color." The just-discussed textiles are a large part of this colorfulness, as the yarns, historically died by natural means that involved plants, minerals, and even insect larvae, sport a vast array of shades from deep magentas via red to yellows. Colors are in every market—just look at all those fruit! The tuk-tuks as well as the so-called chicken buses are painted in vivid greens, reds, and yellows, as are the boats, the lanchas. Bare walls are begging to be adorned by colorful murals, not the usually subdued (and stupid) graffiti that we see in our cities and those in Europe. The sky is a deep blue, the mountain sides are a satisfying green, and when there are clouds they are a brilliant white. Color is everywhere, and maybe that's why the people have such bright countenances.

Resisting the urge to weigh myself for a quetzal in plain view of everyone I found a spot in a restaurant overlooking the lake. From an adjacent restaurant the noise of an ongoing World Cup soccer quarterfinal was trying to out-do the loud sounds of our jukebox. There probably were some gringos around, but they were not noticeable among the locals who were out on the town on that beautiful day. Feliz Navidad, indeed. I encountered a similar scene, just not as pronounced, on an excursion to San Pedro: pura vida, as they call it in Costa Rica. Once in a while people just like and want and need to let their everyday life slip away for a few hours.

I cannot say that I had a particular "favorite excursion" during my week on the lake as every single one was so different and full of impressions. But when it comes to the toughest and maybe most rewarding outing, I think it was my hike up to the Mayan Nose. I had read up on guided tours to some of the surrounding volcanoes (Guatemala is home to 30+ of them), but too many online comments as well as what Byron had told me convinced me to not pursue such a trip. Apparently there have been instances of hikers being accosted and robbed in the upper portions of these regions, despite being accompanied by local guides. Even though most of the area is a national park, law enforcement is light at best and there are just too many opportunities for a few bad elements to slip in and out.

Imagine a Maya lying on his back, nose facing upward (viewed from the

other side of the lake a few days before my climb)

other side of the lake a few days before my climb)

|

| La Nariz as seen from the trailhead |

Byron had suggested I contact a local entrepreneur, Luis Tuy, to arrange for a less-dangerous excursion, and via WhatsApp we settled on a hike up to La Nariz del Indio. Numerous tour operators offer this hike to coincide with the sunrise over Lake Atitlán, but I wasn't too keen on getting up at 3 a.m. Instead, Luis picked me up in his tuk-tuk at 10 a.m.; also onboard was his younger brother Francisco, who was going to be my guide for the hike. The tuk-tuk drive took about half an hour to the outskirts of San Pedro, where the trailhead is located. I paid my national park entry fee, and then the climb began. From the shores of the lake to the top of the Nose it is a little more than two miles, but at the same time one gains just shy of 2,500 feet. Dude, that's steep! Quite a few of the sections appeared to be close to vertical, where one had to use both hands and both feet to make it up.

I was a bit concerned about having to come back down this way as my artificial hip definitely felt the effort. However, Francisco, a kid of 24 who weighs less than 100 pounds, assured me that I would be OK and that we would use a different, easier route. He had estimated that it would take us two-and-a-half hours to reach the top, based on his experience as a local guide with gringos in tow, and he was surprised when we made it in a little less than two. Of course, this involved numerous stops, either to just catch my breath and rest the hip or to snap yet another pic from a scenic spot. I tell you, the view is simply spectacular, and we were lucky that the sky stayed mostly clear of clouds until the early afternoon.

After about 45 minutes at the top of the Nose (the name stems from the resemblance of the formation to an Indian's face seen in profile in a supine position) during which I gorged myself with the 360° views of lake and mountains we finally started the trip back down. However, instead of heading back to the lake we continued to Santa Clara de Laguna, just a few hundred feet lower than the summit and connected with a much more shallow path. (This is also the route that the sunrise hikers take up to the Nose.) Francisco texted his brother, and we were met by Luis in the tuk-tuk. On the way back to Tzununá we stopped for an obligatory heroes' photo. The whole excursion, with transportation and a private guide, including a nice tip, cost me less than $45. Luis asked me whether I would plug his services, and I am glad to do so. Should you find yourself in the area, you can reach him through https://g.page/r/CT4G5mVf8oHKEBM, which will take you to the Luituy website. (I don't want to lose you here, so just copy and paste.)

As you can see, there was much to see and experience during that week on Lake Atitlán, arguably the most beautiful lake in the world. I can easily see myself returning here for a quiet week or two. There are enough foreigners who have already discovered the magic of this area, and one can only hope that change will not come too quickly.

My final two days in Guatemala were spent in the old capital of Antigua, and I will cover that part of my trip in a third installment within the next few days, so please come back. Feliz Navidad!

My final two days in Guatemala were spent in the old capital of Antigua, and I will cover that part of my trip in a third installment within the next few days, so please come back. Feliz Navidad!

No comments:

Post a Comment